The VIX Ascendant?

Regardless of your political affiliation, almost everyone would agree that President Trump is an industrial strength disruptor. With disruption comes uncertainty, and uncertainty is the lifeblood of implied volatility.

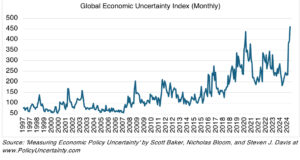

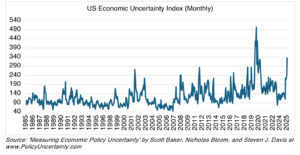

Recently, I came across the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, which is an index constructed from the volume of newspaper articles mentioning policy-related economic uncertainty, as well as the number of federal tax code provisions set to expire and disagreement among economic forecasters. It’s calculated on a country-specific basis as well as globally. Below are the monthly results for the US and globally:

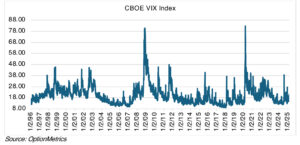

Other countries display similar results – as of January, economic uncertainty was the highest it’s ever been on a global basis. This would seem to be the perfect environment for the most common fear and anxiety gauge, the VIX. For those requiring a short refresher, the VIX is the CBOE volatility index, and is derived from 30-day put and call options on the S&P 500 Index (SPX).

Last Thursday, the VIX broke the 20 mark for the first time this year (charts below). Just yesterday, the VIX jumped to a high of 24.69 on tariff fears, the highest it’s been since last December. For context, it was only 14.77 as recently as February 14th. In addition, the volatility of the index itself (as measured by the VVIX, the volatility of the volatility) has been increasing as well.

It would seem that the combination of general Trumpian uncertainty and a possible shift away from an AI-dominated market (see below for more on Nvidia) have contributed to a heightened VIX. The “Trump Bump” is officially over, and the effect of many of his administration’s policies, mostly tariffs, on the economy is worrying investors.

Keep in mind that as the market declines, the VIX tends to increase. There are some technical reasons for this, but mostly it is due to the perception that downside price variance is greater than that of the upside. In other words, the downside is scarier than the upside. The inverse relationship between price and volatilty is true for many individual stocks and commodities as well.

One important note about the VIX – it’s frustratingly sticky to the upside, and once elevated, it tends to revert to the area from which it came. Like many other markets, it requires new or amplifying news to remain inflated; otherwise, it tends to drift lower. The message for those looking to profit from a VIX spike: don’t wear out your welcome.

Nvidia: Here We Go Again!

Yes, I’ve written about Nvidia vol crush a million times, but it’s something that all traders and investors should be familiar with, namely that you don’t have to be a great price forecaster to make money on options. There is another game in town.

Last Wednesday, Nvidia announced earnings after the bell. As usual, they exceeded expectations, spectacularly so, with revenue up 78% and EPS up 84% year over year. For almost every company out there, such news would be greeted with cheers, streamers, and party hats. But, this isn’t just any company, it’s Nvidia, and those rules don’t apply anymore. As I explained last blog, spectacular results are old news for Nvidia, and the market has come to expect, and even ignore, them. Rather, the market is now looking for reasons to doubt the “Nvidia AI Dominance” narrative. Hence, NVDA’s 17.5% decline year-to-date and it’s almost 8.5% plunge after its latest earnings announcement. Fundamentals change, and it’s important to know what’s in, and more importantly, what’s out.

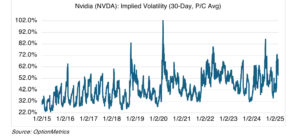

Regardless of how the market feels about NVDA, vol crush is still alive and well. As you can see below, NVDA implied volatilty last Wednesday, the day of its earnings announcement, was running 63.1%. As of Friday’s close, it was down to 54.2%, a decrease of almost 9 vol points.

I reviewed Nvidia earnings announcements going back to February 2015, all 42 of them. In all but one case, NVDA implied volatility decreased the day after the announcement by an average of 10.4 percentage points. You don’t see that amount of one-day vol movement all that often, much less 97.6% of the time.