Prediction Markets and Options

One of the most significant events in financial markets over the last several years has been the rise of prediction markets. Markets that trade bets on the outcome of various events have existed in one form or another for hundreds of years. From betting on papal successors in the 1500s, to presidential elections starting in the mid-1800s, to the Hollywood Stock Exchange in the mid-90s, prediction markets have a long history. Increased acceptance of online sports betting, as well as a looser regulatory regime, have propelled them to new heights. Today, Polymarket, Kalshi, PredictIt, ForecastEx, and other platforms offer markets in sports, entertainment, politics, culture, finance, and just about anything else that can be called a bet. Monthly volume (mostly sports betting) is estimated to have risen from less than $100 million per month in early 2024 to more than $13 billion by the end of last year. More than $1 billion was reportedly traded on Kalshi during Super Bowl Sunday.

Of interest to participants in the financial markets, and particularly to futures and options traders, is that financial and economic offerings on prediction markets have expanded rapidly. This is partially due to the fact that regulatory barriers have decreased and partially clarified. Since they have been deemed to be financial markets, or more specifically Designated Contract Markets (DCMs), the CFTC has claimed regulatory authority at the federal level, superseding state authorities (although state regulatory authorities continue to question the CFTC’s claims of jurisdiction over sports betting). The CFTC also signaled support for the continued development of event contracts and withdrew proposals that would have limited political and sports event offerings. Established exchanges have reacted accordingly: ICE has invested up to $2 billion in Polymarket, and the CME is offering their own prediction markets on various equity indexes, economic indicators, and commodities.

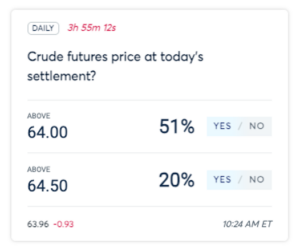

Regardless of the platform, all prediction markets offer one main product, event contracts. There are variants, but they all work basically the same way. Each event contract is in the form of a yes/no question. The maximum you can make on each contract is a set amount, usually $1.00. Depending on your prediction of the outcome, you can then bet “yes” or “no.” Here’s an example using crude oil from the CME:

Source: CME

In this case, suppose you decided to bet that crude futures will close above $64.50 by the end of the day (the exact conditions are specified). Given the latest prices, that will cost you $0.20 cents. Stated another way, you are betting that the probability is greater than 20%. If it turns out that it does indeed close above $64.50, then the maximum you could make per event contract is $0.80 cents ($1.00 – $0.20). If it doesn’t, you lose $0.20 cents, the entire investment. You don’t have to hold the contract to expiration; if it goes up, or you change your mind, you can sell it and it will be cash settled. Like ordinary futures or options, you can trade in and out as many times as you want.

Like many successful financial products directed to retail investors, event contracts are really just a repackaging of a product that has been available for some time to institutional investors. Binary options, which are usually considered exotic derivatives, are functionally the same as event contracts and have been around since the 1970s. Like event contracts, binary options feature an all-or-nothing payout conditional on the result of a specific yes/no question tied to an event or price.

Although the basic contract and payoff structure are the same, binary options were confined to institutional and high net worth investors. In contrast, event contracts are geared to retail participants and to those that would never consider trading conventional futures or options. Their simple easy to understand structure and limited downside risk make them extremely attractive to those accustomed to sports betting but willing to try something new. For those who currently 0DTE options, the jump to event contracts is easy to understand.

Since event contracts and binary options are functionally the same, theoretically they should be able to be arbitraged. Practically speaking, this is difficult due to wide spreads in both products and limited volume preventing efficient execution. Arbitrage within event contracts themselves is also theoretically possible since it is possible to sell “yes” or “no” opinions. For example, selling “yes” and buying “no” produce the same risk/reward profile, so the two should be priced equivalently. Again, due to wide spreads, limited volume, and fees, this is difficult in practice.

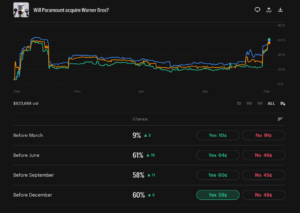

Although they are a much simpler product than conventional options, event contracts do offer one key advantage for both institutional and retail participants. For certain events, such as potential M & A activity, event contracts offer a purer way to trade the event. The rivalry between Paramount and Netflix to buy Warner Brothers is instructive. Event contracts allow you to make a pure bet on who will ultimately prevail and when. Here’s an example from Kalshi:

Source: Kalshi

Of course, you could try trading the acquisition using conventional options on Warner, Paramount, or Netflix. However, that’s not a pure bet on the acquisition; there are many theoretical reasons why the participants’ stock prices could change other than due to the potential acquisition. In addition, the timing of the deal is extremely difficult to predict. As a result, and even if you use short-dated options, you cannot infer the acquisition’s probability of success using conventional options. You can get close, but prediction markets offer a more accurate assessment.

However, there are three significant downsides that may limit the continued development of prediction markets. First, and especially for institutional players looking to hedge against certain events, practically speaking there is not enough volume to do so effectively. For the time being, event contracts are a retail product. Second, for certain event contracts, the specter of insider trading and market manipulation hangs over the market. For example, economic releases, such as GDP, unemployment, and inflation, now have increased potential to be traded directly and easily by those with advance and inside knowledge of the result. This has reportedly already occurred in certain contracts regarding events in Venezuela and Israel. And third, although the regulatory regime is becoming clearer and the CFTC is supportive, state authorities continue to assert jurisdiction.