Overpriced SAF?

Although most people take them for granted, large commercial airliners are pretty incredible machines. Take the Airbus A380, the largest commercial aircraft in the world. At about 240 feet long and almost 80 feet high, its takeoff weight is 1.1 million pounds. It takes four jet engines with a combined thrust of 280,000 pounds to get it in the air. All that requires a lot of jet fuel — the A380 burns an average of 4,600 gallons an hour and has an overall capacity of 86,000 gallons.

Admittedly, the A380 is an extreme example of a commercial airliner, but I bring it up to point out the challenges the airline industry faces when it comes to meeting sustainability and net-zero emissions directives. Besides the extreme energy requirements described above, keep in mind that commercial aircrafts last an average of about 20 years and are a significant capital expense. Any near to medium term solution will therefore require minimal changes to existing aircraft.

Enter SAF, or sustainable aviation fuel. Technically, SAFs are alternative jet fuels that can obtain a 50% reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gases. They aren’t made out of hydrocarbons, but instead use municipal solid waste, animal fats, oils and greases, algae, crop residues, and wood biomass as feedstock. SAFs are a “drop-in” fuel, and unlike more complex technologies, are currently compatible with today’s jet engines and aircraft.

The Biden administration’s aim is to have enough SAF to meet 100% of aviation fuel demand by 2050. That’s a tall order: total global jet fuel demand is roughly 53 billion gallons a year, but only 26 to 32 million gallons of alternative fuel were produced in 2021. That’s a miniscule 0.05%. In the US, only 4.5 milliongallons were produced, or 0.02% of total US demand. When you consider that SAFs are currently 2 to 4 times as expensive as traditional Jet A, that’s not surprising. In addition, feedstock limitations may prevent SAF from ever approaching the scale necessary to provide a significant contribution. However, SAFs may be part of a solution to reduce aviation emissions, not the magic bullet, single solution.

The Inflation Reduction Act included a SAF tax credit to jumpstart the industry. Most SAF producers are startups, working on new processes to lower costs or increase production. Among them are SkyNRG, Fulcrum BioEnergy, Alder Fuels, and World Energy. The industry leader, and the only one that is public, is Gevo (GEVO), which has the advantage of strategic partnerships with Phillips 66, LG Chem, and ADM, supply arrangements with American Airlines, and proven technologies.

If you’re building a portfolio of green technology firms on the theory that just a few of them may catch fire, then you may be interested in SAF leader Gevo (GEVO).

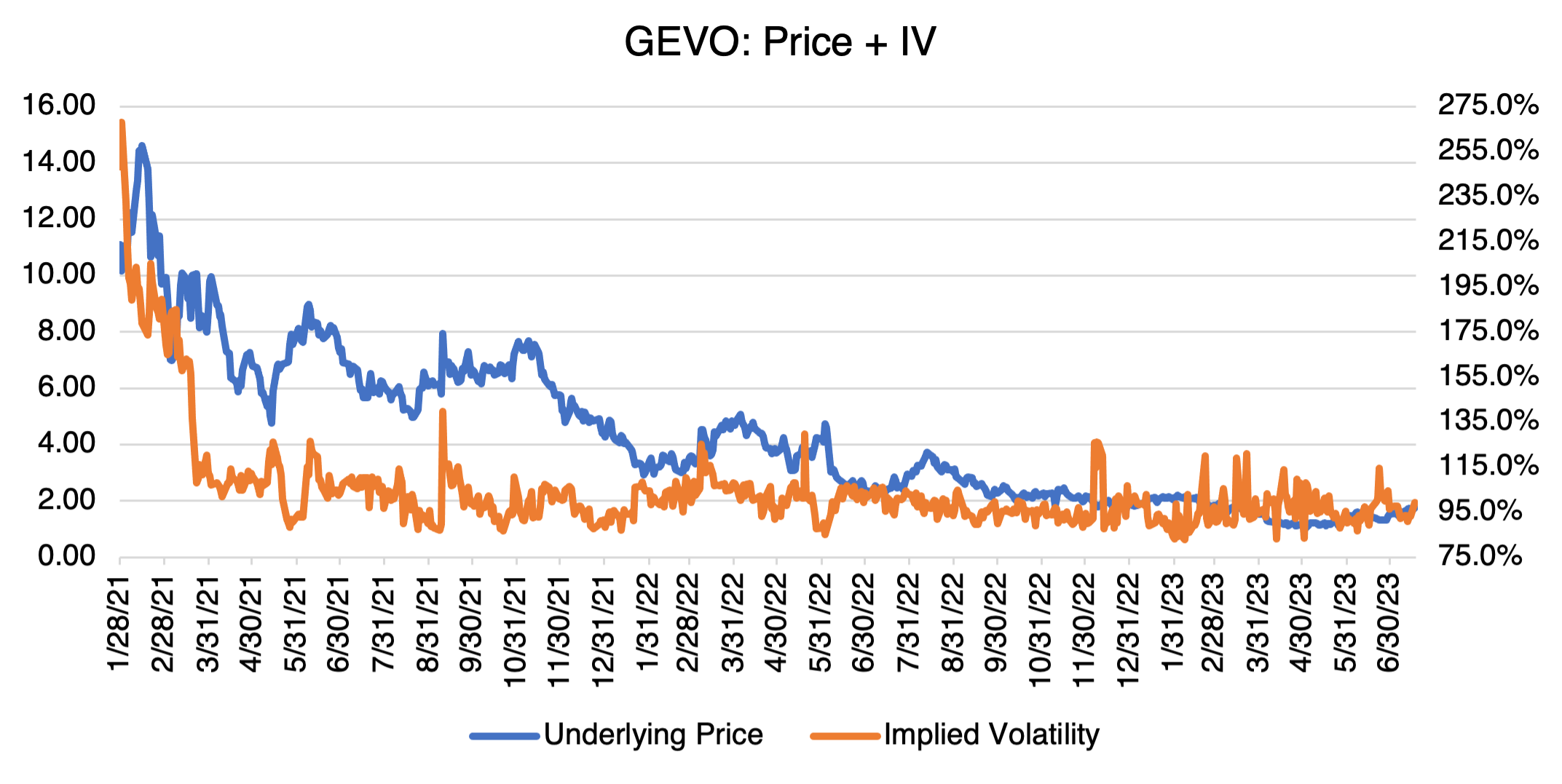

Before doing so, however, keep in mind that options on Gevo are very expensive and regularly trade over, or near, 100% implied volatility. In addition, there’s something interesting and instructive going on here. 30-day historical volatility, or the annualized standard deviation of the logs of the returns of the last 30 days, is currently 77.2%. With 30-day implied volatility at almost 100%, that’s almost a 23% spread over historical. Although the two should not be equal (for a variety of reasons, but mostly because implied is forward looking and historical is backward looking), the spread is extremely wide. I suspect that is due to the lack of volume. Options are not always the most appropriate instrument. If GEVO still appeals to you, the underlying stock is a better value.