Is the Solar Party Over?

If you own a home, then you’re familiar with the person who shows up at the front door trying to sell you solar panels. Where I live, it’s almost a weekly occurrence. Which got me to thinking – given the administration’s hostility to green energy subsidies and favorable regulation, how are residential solar companies faring? And more specifically, what’s going on with rooftop solar loans, i.e., the loans residents use to buy the panels in the first place?

The answer became apparent last June 8th, when Sunnova Energy, a large rooftop solar installation and finance business, filed for Chapter 11. Saddled with debt and running out of cash, they could not secure additional funding. Shortly before that, Solar Mosaic, another solar panel finance company, also filed for bankruptcy. Other installers called it quits in 2024. What’s going on with solar finance?

A mini-2008 debt crisis, that’s what. In 2024, about 50,000 houses had solar panels installed, up from 14,000 in 2019. About 58% were financed, and 23% leased. Easy credit, tax credits, and lower panel prices fueled the demand, as well as aggressive door-to-door sales techniques. Nonbank lenders, who initially financed the panels but then sold the loans to banks and private-credit firms, led the charge. Loans were then bundled together into asset-backed securities (ABS), most of which were rated investment grade by the ratings companies, and then sold to investors. Just like any asset-backed security, the return is ultimately predicated on consumers servicing their debt. If default rates turn out higher than predicted, greater than expected losses flow up the daisy chain.

Easy money usually involves lower credit standards and lower quality borrowers. Eventually, the music stops when these same borrowers start defaulting. And that’s just what’s happening, as many consumers (who should probably have never gotten a solar loan in the first place) can no longer afford to service their loans. Some of the solar-backed bonds that were sold at 100 cents on the dollar in 2022 are now worth 42 cents.

Does this feel eerily reminiscent of the mortgage-backed crisis of 2008, only a much smaller scale? It should, but fortunately, the sector just isn’t big enough to trigger a systemic problem. But it’s still scary. It’s been 15 years since the mortgage-backed crisis that kicked off the worldwide financial crisis. Apparently, some lenders and their backers have forgotten that easy credit combined with mass marketing does not end well.

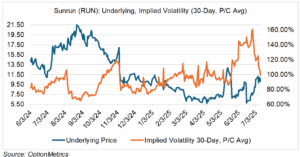

On top of the higher defaults confronting the residential solar industry, higher interest rates, the elimination of the residential solar tax credit, and higher panel prices are all adding up to reduced demand. Particularly affected by this should be Sunrun (RUN), a company that derives 85% of its revenue from the manufacture and installation of residential solar systems. As its recent history indicates (see chart below), its implied volatility spiked into the triple digits when prices started decreasing in mid-May. Since then, prices have recovered somewhat and RUN’s implied volatility has declined to just under 100%. If the stock resumes its bearish run, then I suspect its implied volatility will spike back up.

Jane Street Shenanigans

If you trade options, then I’m pretty sure you’re familiar with the Jane Street/India trading brouhaha. To summarize, the Indian regulator, SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India), is accusing Jane Street of index manipulation, froze $566 million in allegedly unlawful gains, and barred them from trading (the order, all 105 pages, may be found here).

If you’re not familiar with Jane Street, it’s a NY-based quantitative trading firm (despite some reports, it is not a hedge fund – it trades solely with its own capital and does not manage outside money). Reportedly, from January 2023 to March 2025, Jane Street made $4.3 billion trading in India. That’s a lot of money in anyone’s book, and enough to grab the attention of regulators, especially when a foreign entity is involved. Social media is awash in comments characterizing Jane Street as greedy colonialists, eager to exploit the riches of empire.

What did Jane Street allegedly do? To start, it involves options trading in India. Little known fact: the Indian options market is gigantic, and by volume (not value) is by far the largest options market in the world. In 2023, it traded 85.3 billion contracts; in the same year, the US traded 11.2 billion (interestingly, Brazil is #3 at 2.4 billion). Apparently, Indian options traders, who dominate the market, love the leverage that options can provide.

On options expiration days, the Indian options market dwarfs the cash and futures markets for the underlying stocks. This perverse fact is at the center of SEBI’s allegations:

“…on weekly index option expiry day, by aggressively influencing the underlying cash and futures market with significant volumes (relative to those markets), a group of entities acting in concert with adequate funds and capital at their disposal, can influence and manipulate the index levels. This in turn can allow them to put on significantly larger and profitable positions in the highly liquid index options market by misleading and enticing large number of smaller individual traders. It could also be used to engineer the closing of the market on expiry day in a manner that benefits enormous index option positions that they may be running to expiry.”

In short, SEBI maintains that Jane Street manipulated the market by pushing around the relatively illiquid underlying index to influence options prices to their advantage. Of course, Jane Street vigorously disputes these allegations, calling them “erroneous or unsupported assertions,” and asserts that it was just legal index arbitrage that maintains market efficiency.

As usual in such cases, one man’s arbitrage is another’s manipulation. The alleged strategy wasn’t that complex – trading between options and their underlying is pretty standard stuff and usually intuitive. What will be complex is proving manipulation and intent.

I suspect both parties are right to a certain degree, but there aren’t enough facts yet to draw any definitive conclusion. In the meantime, the allegations aren’t doing wonders for Jane Street’s reputation, and I suspect other regulators are taking a look at what the firm has been up to over the last several years. For SEBI, they now have a chance to shape new legal definitions of manipulation that could have worldwide ramifications.

A great twist: SEBI started investigating JS as a result of media reports published during April 2024 regarding a lawsuit, started by Jane Street itself! It seems that some employees decamped from JS and went to Millenium. JS sued, alleging that they stole trade secrets. As part of the suit, it was revealed that the traders in question were employing a strategy in India, and that it was extremely (almost unbelievably so) profitable. That got SEBI on the case. The Shakespearian phrase “hoist with his own petard,” comes to mind (look it up!).