Beware of the “It’s Cheap!” Trap

At one point in my career, I was the risk manager for an absolute return hedge fund. For those of you who aren’t hip to cool kid hedge fund lingo, an absolute return hedge fund is supposed to make as much money as they can. If you thought that was the case with all hedge funds, you wouldn’t be mistaken, but people love to label things.

In any case, the portfolio manager (or “PM” as they’re known), was fond of pointing out deep out-of-the-money options and yelling, “I can’t believe they’re so cheap! They’re all idiots!” I’ve heard the same opinion from other options traders, that low-priced options (i.e., options with a small premium) are “cheap” and therefore should be scooped up.

Although it might sound pedantic, it really depends on what you mean by “cheap.” In the case of my PM, what he really meant was that he was bullish on the stock in question and therefore the option seemed cheap compared to where he thought the stock would eventually trade. Since options contracts are leveraged (i.e., 1 contract represents 100 shares of stock), that’s true to varying degrees for all options contracts. In this context, the statement isn’t very informative — all he’s saying is that he’s bullish or bearish.

Much better is how experienced options traders view the cheap or expensive question. In almost all cases, they are not talking about the absolute price of the option (i.e., the premium), but rather about their favorite topic, volatility. This isolates the analysis of the option’s current price from any potential future price movement. In other words, confronted with thousands of similar options, volatility helps them to assess their relative value.

How do they do that? Using historical data, they assess the general level of implied volatility, and second, they assess the relative implied volatilities of different strikes. In other words, they look at the relative value of the market in general and then the relative value of individual options and strikes within the market.

For an example, let’s review options on Tesla (TSLA).

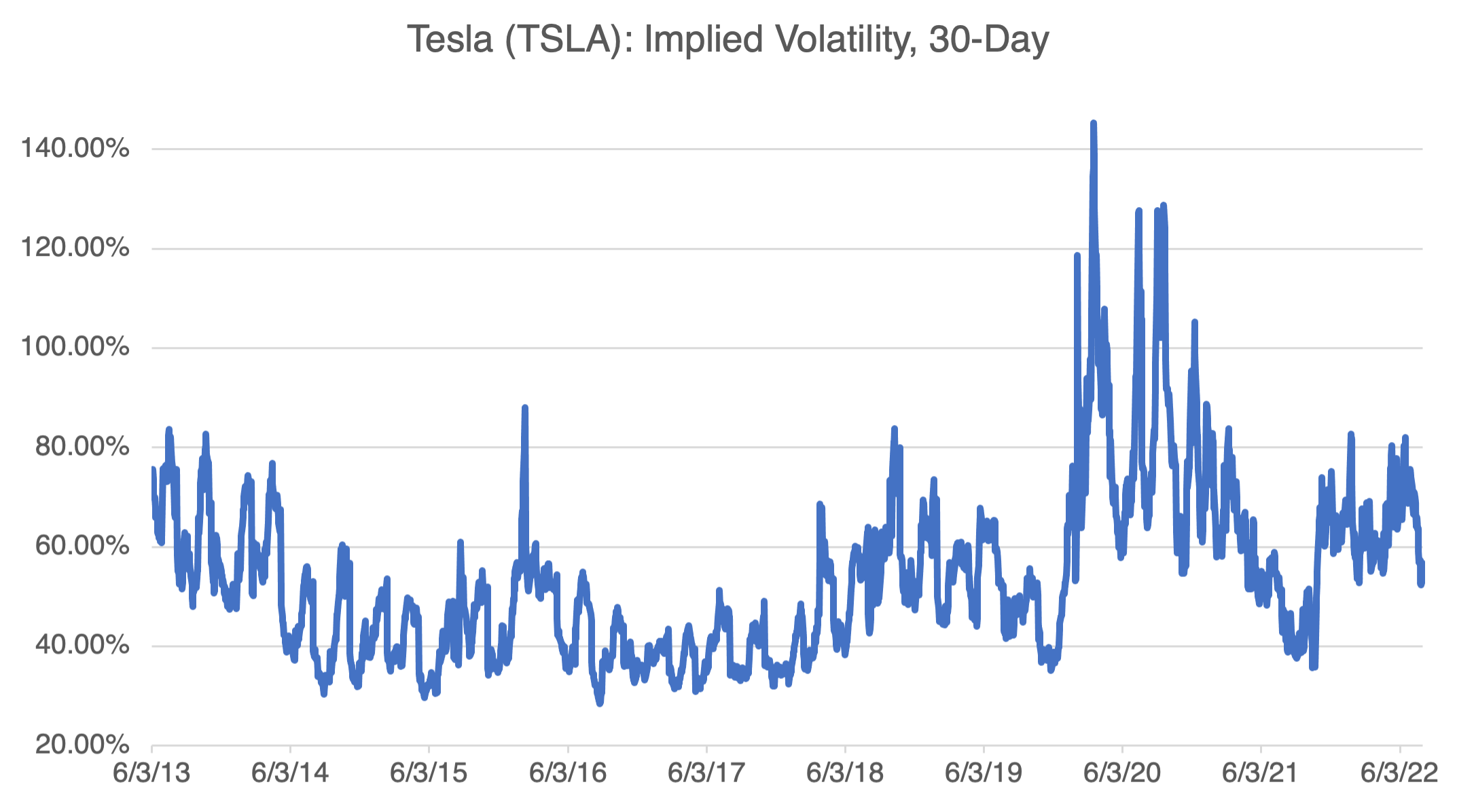

First, let’s review where TSLA options are in terms of relative value, historically. Tesla’s average implied volatility since mid-June 2013 is approximately 54% with a standard deviation of 17%. It’s currently trading 57%, making it toward the top of its “usual” range, but more or less in the middle of its historical range. Therefore, options are neither cheap nor expensive. If implied volatility were trading above 80%, then we could conclude that TSLA options were relatively expensive historically and to exercise caution when leaning to the buy side.

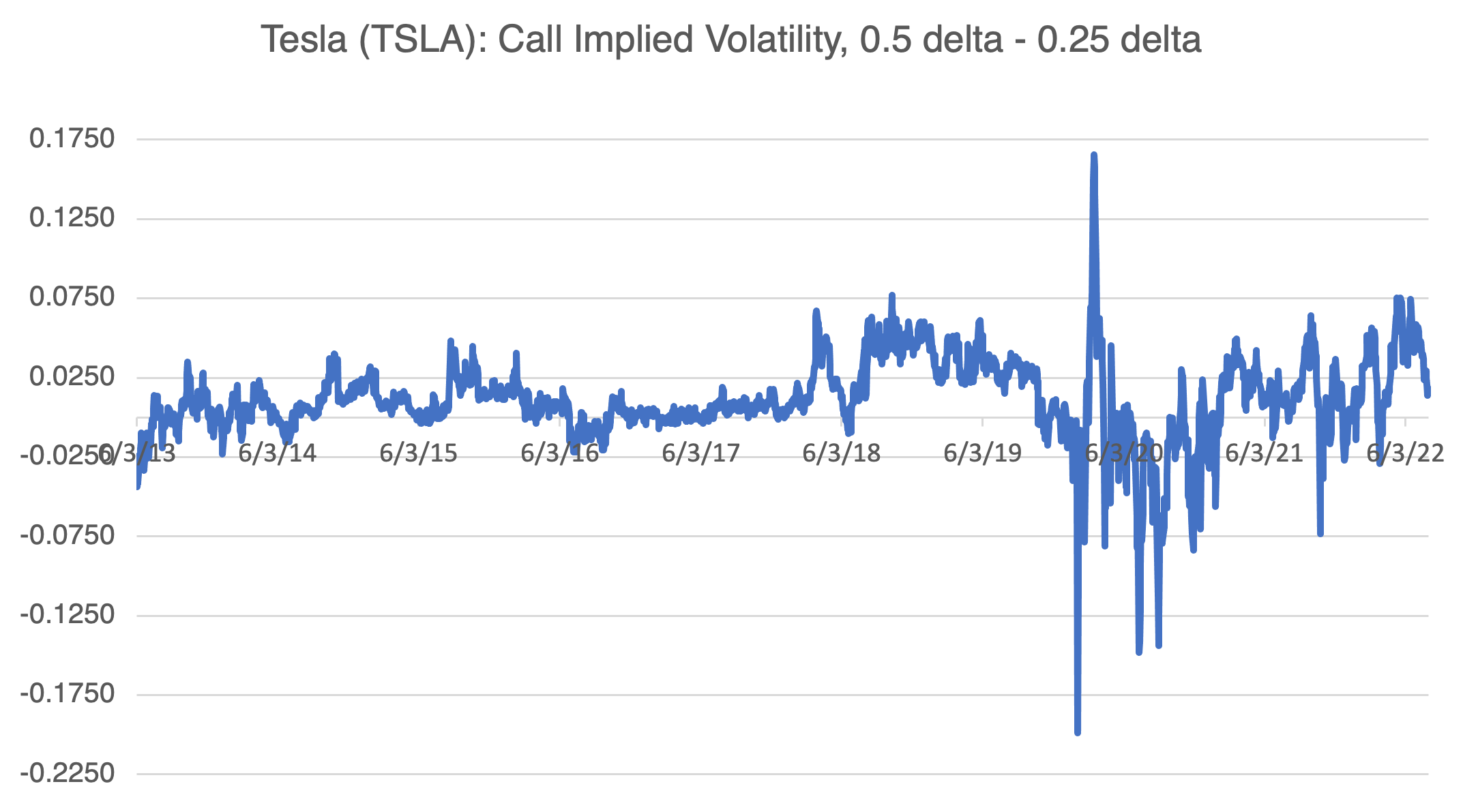

Next, let’s review the relative value of individual options and strikes. The chart below shows the historical implied volatilities of two different call strikes, one at-the-money (0.50) and the other out-of-the-money (0.25). The difference between the two is called “skew” and varies as the stock price and average implied volatility changes. High and low skews indicate the level of demand for out-of-the-money options. For example, since mid-June 2013, Tesla’s call skew has averaged 0.0108 with a standard deviation of 0.0259. Currently, the skew is 0.0180, close to the average figure, but unremarkable. For the sake of argument, assume that the skew was over 0.03 and trending higher. That would indicate that the out-of-the-money strikes were in demand and relatively expensive compared to at-the-money strikes.

Even if both metrics were indicating that the options were expensive, that is not to say that buying the calls in question won’t make money — they surely will if the stock goes up or if implied volatility rises. Rather, the point of the exercise is to determine whether the options in question are expensive or cheap historically. That doesn’t mean that something that’s relatively expensive can’t go up. As anyone that has ever bought real estate can attest, it can.

The China Syndrome

Hysteria gets clicks, so it should come as no surprise that Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan got a lot of attention. China has been ratcheting up tensions over Taiwan for some time with aggressive military exercises, cyberattacks, and threats. Before she landed in Taiwan, predictions of what the Chinese would do ran the gamut from the publication of even more bellicose articles in the Chinese press, all the way to shooting down Pelosi’s plane. Despite the white hot rhetoric, China’s response has taken the form of even more and larger military exercises (for the time being). Suffice it to say that the trip did not cause WWIII to break out.

But…let’s just say that the Chinese had used the trip as a pretext to begin open and unlimited hostilities and the US elected to defend Taiwan. It’s not as improbable as it seems; both sides have been signaling their intentions for years. If this happened, the Ukrainian war would go down in history as a mere dress rehearsal for what came next. China, despite the fact that it has no actual battlefield experience in a modern war, has an extremely large arsenal of high-tech weapons that could prove very problematic for the US. Added to the fact that Taiwan is in their backyard and that we would be forced to eject them if they successfully landed, and we would be confronted with a military situation that we might not be able to win without serious escalation. Although I’m not a fan, former President Trump had it right when he reportedly said, “Taiwan is like two feet from China,” Trump told one Republican senator. “We are 8,000 miles away. If they invade, there isn’t a f***ing thing we can do about it.”

Pundits reassure us that the probability of the Chinese escalating the Taiwanese situation to war are slim and that the two countries have way too much to lose to come to blows. However, the decision to go to war is rarely rational and is usually based on misconceptions, bad information, miscommunication, accidents, and sheer ego. WW1 made no sense at all for any European nation, and yet it broke it out in August 1914 despite the fact that the participants were presented with numerous opportunities to back down. That didn’t happen, and there were hundreds of reasons why it should have. Unfortunately, the current situation with the Chinese could devolve into a similar beginning: an old order and a new order stumbling into a messy and lengthy war that neither wanted that sprung from a disagreement that few will remember after it’s all over.

And now the big question: why am I writing about this in the OptionStrat blog? What does any of this have to do with options? If you’ve been reading this blog for some time, you know that I’m not a hysteric, nor am I into wearing a hard hat outside just in case I get hit by a meteorite. But China/US hostilities are slightly different, in that I fear that their probability is higher than most people think, and that the frequency of hostile events and rhetoric seems to be rising. Of course, both sides could exchange initial blows and then back down from the brink through a negotiated settlement. But that takes time, and major hostilities will have occurred before then. If war does break out — whether by accident or not, limited or not — it might prove to be one of the major events of the 21st century and will dwarf all other considerations and events for months, or even years, to come. It’s a very low probability/major effect event, the stuff that keeps risk managers like me up at night. Something wicked this way comes — maybe and making enough noise to make me lose sleep.

In addition, the effects on financial markets, and by extension options trading, will be off the charts and very difficult to predict. Russia/Ukraine is instructive in that the effects of the war have been disproportionate to the combatants’ economic size. Now, imagine the effects from the two largest economies in the world going to war. That’s very scary, and the effects are almost too large and widespread to predict with any degree of confidence. I don’t pretend to know what they will be but suffice it to say that the effects will be extreme, long lasting, and unexpected, and might even rival the disruptions felt during the 2008 financial crisis.

I would be remiss if I didn’t stress that the probability of all this is extremely low. However, I would also be remiss if I didn’t point out that the probability of a conflict is rising and should no longer be dismissed as outlandish speculation. It’s too important to ignore.